Is there a Vaccine for Teacher Bias— the Other Virus in Public Education?

April 7, 2021

Is there a Vaccine for Teacher Bias—the Other Virus in Public Education?

Holly Benson wanted her child to receive a robust primary education. Ideally, she wanted the learning to occur in an elementary school with a diverse student population and a teaching environment that would preserve her child’s creativity, self-esteem, and sense of worth. From kindergarten through first grade, Holly (who is British) and her husband (who is African American) enrolled their biracial son in an affluent private school in the suburban area of Alpharetta, Georgia. Their son’s years at the private school were uneventful and he seemed happy.

Holly Benson wanted her child to receive a robust primary education. Ideally, she wanted the learning to occur in an elementary school with a diverse student population and a teaching environment that would preserve her child’s creativity, self-esteem, and sense of worth. From kindergarten through first grade, Holly (who is British) and her husband (who is African American) enrolled their biracial son in an affluent private school in the suburban area of Alpharetta, Georgia. Their son’s years at the private school were uneventful and he seemed happy.

Although the Bensons were satisfied with the instruction their child received in the private school, a critical piece on their wish list was missing. The private school lacked the diversity they sought. So, for second grade, they took a leap of faith and enrolled their seven-year-old son in a diverse public school system located in an affluent area of Gwinnett County, Georgia.

After several weeks in his new school, the Bensons noticed a dramatic change in their child’s demeanor. He had become more introverted and less energetic. Holly’s maternal instincts went into overdrive and she wanted to know what caused the sudden change in her son’s behavior. So, she decided to serve as a volunteer at the school and became a self-proclaimed “undercover mom” to unravel the mystery involving his sudden disinterest in school.

While serving as a volunteer, Holly received a rude awakening to some of the subtleties that occur in public schools. She personally observed that some children were more often the last to be recognized when their hands were raised to speak and more frequently scolded for performing simple age-appropriate behaviors such as talking in line or not standing straight. Based on her personal observations, Holly concluded that one prevailing factor determined how the children at the school were treated—”the color of their skin!”

While this was somewhat of a rude awakening for Holly Benson, she is not alone. Many Americans have become “woke” to the other COVID-like “virus” that has crushed the hopes and dreams of children of color in America for decades. That loathsome virus continues to spread distress throughout K-12 public education in the form of teacher bias.

The Harsh Reality

The Harsh Reality

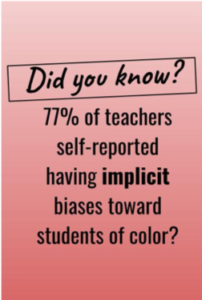

The most dauting challenge for students of color today still involves a form of racism. More specifically, that challenge is related to biases held by teachers. Over 80 percent of the teachers in public education are white, predominantly middle-class females, and most of them are racially biased. Recently, a team of researchers from Princeton and Tufts universities analyzed data from Project Implicit, which collects hundreds of thousands of results from a series of self-administered tests that measure implicit and explicit biases. Responses from nearly 69,000 teachers are included in that database.

The results of the analysis, which were highlighted by the American Educational Research Associates (2020), indicate that teachers are just as racially biased as non-teachers in our society. The researchers found that 77 percent of teachers showed implicit bias as compared to 77.1 percent of non-teachers. Further, they found that 30.3 percent of teachers demonstrated explicit bias as compared to 30.4 percent of non-teachers.

This study sounds an alarm for educators. While the actions of most teachers are well-intentioned, their racial biases continue to adversely impact outcomes for students of color in their classrooms. This is the reality Holly Benson witnessed in her son’s school. White teachers tend to have significantly lower expectations for black students than they do for white students. The harsh reality is loud and clear—our schools are infected with teachers who have racial biases.

The Vaccine

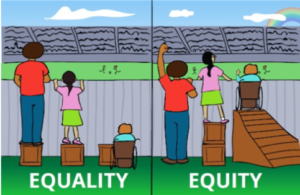

School systems across the nation are in a crisis because racism is gnawing away at the future of many innocent children. Racial inequity is ingrained in our education system, and black children face the most extreme hurdles to academic success. Within individual classrooms, teachers may mistake a black child’s frown as an act of aggression instead of an expression of bewilderment (Taylor, 2021). Scenarios like this often create tensions and, too often, result in a child receiving a senseless suspension from the classroom.

Fortunately, there is a proven strategy or “vaccine” available to address teacher bias. If educators harbor any hopes of ever flushing racial bias from the ever-increasing multicultural classrooms across America, they must strengthen teachers by injecting them with ongoing doses of “high expectations” for all students. According to a comprehensive report by Hanover Research (2019), empirical evidence indicates that school districts can accomplish this by providing implicit bias training for teachers through ongoing professional development.

The future of K-12 public education hangs in the balance. We have the knowledge and a vaccine—implicit bias training—that works. Through this training, teachers are able to confront their biases and move toward having high expectations for all children. Consequently, we cannot sit idly and watch systemic racism in the form of teacher bias destroy the core of America’s future, which is our children.

References

American Educational Research Associates (2020, April 15). Research finds teachers just as likely to have racial bias as non-teachers. In Phys.Org. Retrieved from https://phys.org/news/2020-04-teachers-racial-bias-non-teachers.html

Barber, R. & Corriher, B. (2018, October 11). Honoring Reconstruction’s legacy: Educating the South’s children. Facing South. Retrieved from https://www.facingsouth.org/2018/10/honoring-reconstructions-legacy-educating-souths-children

Hanover Research (2019, March). The Impact of Implicit Bias Training. Retrieved from http://wasa-oly.org/WASA/images/WASA/6.0%20Resources/Hanover/IMPLICIT%20BIAS%20TRAINING.pdf

Taylor, J. & Taylor W. (2021). The Imperfect Storm: Racism and a Pandemic Collide in America; How It Impacted Public Education and How to Fix It (pp. 75-77). Bloomington, IN. Archway Publishing.